Chasing NEOWISE

One of the few bright moments 2020 conjured until now was a new fuzzy-ball-of-fluff visitor zipping across our solar system: Comet NEOWISE. It is the only comet I have ever seen, and the best anyone has seen since 1997. It came at just the right moment too, being visible to the naked eye after the first week of July (a.k.a. the 17th week of March). At a time when life was monotonous (and still is!) with no real short-term goals, and all long-term goals blurred beyond the realm of reality, NEOWISE gave me a tangible target to chase.

Observing and photographing comets is not easy. But unlike meteors, time is on one's side. Comets are occasional visitors to the inner solar system, a.k.a. our neighborhood from the far outer reaches of the Kuiper Belt. Chunks of rock and ice here can get strayed and pulled into the Sun's gravitational potential. As they approach closer, the Sun's heat and radiation causes a comet to vaporise, jetting of a tail of gas and dust that always points away from the Sun. Nowadays, most comets are spotted while they're still comet kiddos far away from us, thanks to powerful telescopic surveys that span large portions of the sky. One such mission is NEOWISE: the Near-Earth Object Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer. It first picked out the star of our show as early as the 17th of March 2020. Many faint-hearted comets, however, do not survive the slingshot trajectory that takes them close to the Sun; they get fizzled out along the way. The larger ones tend to survive, and shine gloriously as they approach the inner solar system, showcasing their fuzzy tails like a well-groomed horse. Even as they approach they Earth, they move pretty slowly across the sky as seen from the Earth, roughly hopping between constellations every few days.

Not a comet!

Not a comet!

They certainly don't zip across the sky only to be seen at opportune moments like above; you're thinking of meteors here: tiny space dust that actually enters our atmosphere and shines due to friction heat. Comets, while much larger, always stay at a safe distance away. The closest comet NEOWISE came to the Earth was 54 million kilometers, a third of the way from the Earth to the Sun! If a comet were to come dangerously close, we would know well in advance, and then, well, it's a problem for another day...

As far as comet NEOWISE was concerned, it would survive its approach to the Sun and turn out to be a treat to watch. It was not easy to track it down, but I cherished every moment of the chase: from catching sight of it the first time, admiring its features through a pair of binoculars, photographing it as a hazy swoosh, going back to it at different times of dawn and dusk, trying to frame against different backdrops, before finally turning a big telescope at it for a closer look. I’ll take you for a ride along all of these moments below:

Part I: First Sight

July 10, 2020

It was 4 am in the morning. Picture me as a brown guy with disheveled hair standing outside my car, both doors open on the driver side, alone in an empty parking lot. My gorillapod tripod was resting on the roof of the car, looking like a mini martian war machine from The War Of The Worlds. I was gazing towards the football stadium through a pair of binoculars, just when a police car pulled in.

The news of NEOWISE captured my attention about a week before, when reports of a new comet having a magnitude less than 2.0 surfaced in the Sky & Telescope email Newsletter. Astronomers use the magnitude system to rank stars in terms of brightness. For historical reasons, it scales opposite to the numerical value: stars visible to the naked eye range from magnitudes 1 through 6, with magnitude 6 being the dimmest one can make out from a good dark site. The Greeks labelled the brightest stars in the night sky as ‘class 1’ stars, leading to the hierarchy that has prevailed to the present time. With more accurate measurements today, the brightest stars actually have magnitudes lower than 1, with Sirius being the absolute brightest at -1.4.

Even in light-polluted city skies, stars of upto magnitude 3 or 4 might be visible to the naked eye. A comet ranking below mag 2.0 hence got me excited. I had literally (albeit passively) waited for a naked eye comet for my whole life, and this one would be brighter than the Pole Star! I was ready to go out and see it regardless of the fact that it would come out here in Oxford MS at around 4 am: alarm clocks are friends when it comes to a promise of good skygazing. Alas, the astronomers’ number 1 nuisance kept me in for a good few days biting my lips: a thick layer of cloud cover refusing to budge. (I put the bright moon at number 2 on the nuisance scale since, well, it’s a pretty celestial body to look at by its own right)

Anyway, the clouds cleared up and I cheered up around July 9th, when I began scouting for a good observing location. I knew NEOWISE would be visible very low on the horizon for about an hour before sunrise along the North-East. I needed to make sure I could find a place spread out flat enough so that no trees of obstacles stood tall in that direction. I thought I had just the right place, a huge parking lot next to the new gym building, the south campus rec center. There was even a little hill leading up to a water tower right opposite where the comet would be, so that I could elevate myself (and my hopes) to see it.

So the stage was set at dawn on July 10th, and I woke up dutifully with no snoozes on my alarm at 3:30 am. Armed with my camera, tripod and my new perfectly named celestron cometron binoculars, I set out on the short 5 minute drive to the spot. With no one else around, I rode up the little hill right up to the gates guarding the water tower, with ‘No trespassing’ and ‘cameras monitoring’ signs around. ‘Heck, I can easily explain myself if anyone ever catches me!’, I thought, and turned my eyes to the North-East. My heart immediately sank.

You see, parking lots have floodlights. A lot of really bright white fluorescent lights to shine on zero cars parked out there. They completely outshined any stars towards the East. Except Venus, which stuck out like a small suspended LED above the gym building. I knew Neowise was going to follow a line along Capella, a bright star in the pentagonal constellation Auriga, but I couldn’t make it out clearly.

My options? Waste time trying to drive around searching for another location, or do the next best thing - get in front of one of the lights with enough distance away from the next one so that Capella is visible, hence improving my chances of getting NEOWISE. I went for this, parked my car in front of a streetlight and set up my tripod on it. I focussed my camera using Venus, pointed it in the direction of Capella and took a 13 second exposure. Here’s what I saw:

My first picture: Can you spot NEOWISE?

My first picture: Can you spot NEOWISE?

My first reaction was, ‘Ah well, at least I have the field in focus’. I wasn’t even sure whether NEOWISE had risen enough to pop up above the treeline. When I noticed that sweet little swooshy smudge in the bottom left corner. It was unmistakably the comet! Still invisible to my naked eye, I immediately grabbed my binoculars and pointed to the V-shaped notch in the treeline. And there it was, the first time I registered light from a comet with my eyes! I clicked a few more pictures to zoom into and process later:

I soon realized that I did need to scout for a better location for the upcoming days. I packed my equipment and drove towards the campus. I knew the road leading from the south towards the Ole Miss football stadium pointed in the direction of NEOWISE, and hence could make a good backdrop for a picture. I pulled into a parking lot with that view, and opened both driver-side doors to set my camera up and grabbed my binoculars.

Immediately, I noticed a police car pulling into the lot. I wasn’t too scared, I just remember thinking that explaining all of this could be amusing. I was wary, however, given the on-going political climate and the movement against police brutality. Police here are known to act early on instinct - I was a brown guy with dishevelled hair in a parking lot with my car doors open at 4 am, gazing into the distance with a pair of binoculars and a tripod on the roof of the car. My fears were laid to rest when a young, friendly-looking black cop asked me “what’s going on?”. I genuinely feel more alert and wary when it comes to running into white policemen, while I perceive policewomen and men of color as members of the community out there to help and protect me. I understand this kind of ‘reverse’ profiling is also unwarranted, but it is an accurate reflection of the present state of affairs.

My view from the parking lot where the cop joined me, looking towards and above the lights in the football stadium. Venus looks bright on the right, NEOWISE is faintly visible just to the left of the red light in the middle (download and zoom into the image)

My view from the parking lot where the cop joined me, looking towards and above the lights in the football stadium. Venus looks bright on the right, NEOWISE is faintly visible just to the left of the red light in the middle (download and zoom into the image)

I told the cop that I was trying to photograph a new comet in the sky. Unfortunately, I couldn’t point it out over the football stadium, because guess what, the parking garage in front of it was full of lights. It was visible to my trained eye through the binoculars, but there was no time to waste convincing the cop that I was looking at a real thing in the sky. Thankfully instead, he turned my attention to Venus, shining brightly, and asked me what it was, since there was no way it could be a star! I happily described our closest neighbor, and said that the lights were a nuisance for trying to see the comet. The cop then gave a pretty good suggestion that had already crossed my mind before, but hadn’t registered: “Have you tried going up on the roof of the parking garage?”. I remarked that it would be a good place, but not for the campus garage. I was thinking of the new one they built next to the town square, which had fewer lights up top. The cop said it was really cool to see Venus, and moved on acknowledging that he won’t waste more of my time.

I had already made up my mind against staying in that spot to see if the comet rises further away from the lights. But I waited until the police car pulled way ahead to pack up and move on. It had already started to lighten (what’s the dawn equivalent of twilight?), and a few clouds were heading eastward. I had probably seen the last of the comet for the day, but it was still worth going to the Square and checking if the garage rooftop was a good location for the following day. That’s exactly what I did: clouds greeted me as I reached the top, but I could already feel that the place was ready to lift the curtains for a second viewing of NEOWISE. Even if I couldn’t knock out the couple of lights in the corner of my eye.

Part II: Morning Glory

July 11, 2020

When a pair of soft, warm, melt-in-your-mouth, first batch of the day doughnuts only appear as an afterthought in the recollection of a morning, you know something really special preceded it.

The garage rooftop I found the previous day turned out to be a great location. The sky was clear, and the waning moon was hovering over the west, above the Oxford courthouse. To its left was Venus shining bright among the large star cluster in Taurus, the Hyades. It was as if it was in a competition to outshine Aldebaran right next to it, the red giant star also known as the ‘eye of the bull.’ Draw a line above the two, and you could see the Pleiades, probably the most well-known star cluster which looks like a miniature big dipper to the naked eye.

It was moments before Neowise would rise, and this time, I was not alone in waiting to catch its sight. I had convinced two of my fellow Astronomy TA friends, including my roommate, to set their alarms really early that dawn. Soon, with some nudging, we were all stretching our legs on the rooftop. We warmed up (or cooled down?) our eyes by staring at the Pleiades, making sure they adjusted to the darkness such that seven sisters were visible. Such open star clusters are cradles of star formation, rich in natal hydrogen gas clouds which collapse and ignite to give birth to a star.

After scanning the surroundings for places I can place my camera tripod without the worry of it falling 3 stories below, I turned my binoculars towards where NEOWISE was supposed to be. It took me no time to see it, looking shinier than the previous day. The swoosh of the tail was so illuminated that soon it became apparent even to the naked eye, like an erased chalkboard marking in the sky.

We took turns to have our fill with the sight of our first ever comet. It was now time to take its picture. I wanted just the right amount of rooftops from the quaint North Lamar buildings to flank the bottom of the snap. Any more, and their light would steal NEOWISE’s glory. I focussed my camera using Venus and Aldebaran, and was delighted to see that they could also fit into the view alongside NEOWISE. A stellar picture, indeed! It took a little bit of experimentation to determine the correct amount of exposure, finally settling in on a shutter speed of 6 seconds. It was enough to show NEOWISE’s tail properly, while avoiding too much contamination from the city lights. My plan was to take lots of pictures of the same scene, and then stack them like pancakes. This adds up the pretty light from the stars and the comet, while smoothing out the pesky little specks of noise in each individual picture. I’ll write more in a future post about how stacking works and how you can do it for images featuring stars.

The wide-angle shot featuring (Clockwise from bottom-left): Comet Neowise, Capella in the constellation Auriga, the Pleiades a.k.a the Seven Sisters, Venus next to Aldebaran in the Hyades in Taurus.

The wide-angle shot featuring (Clockwise from bottom-left): Comet Neowise, Capella in the constellation Auriga, the Pleiades a.k.a the Seven Sisters, Venus next to Aldebaran in the Hyades in Taurus.

After a good 20 photos from the wide-angle, all encompassing shot featuring NEOWISE, the Pleiades, the Hyades and Venus, I wanted to take a closer snap of NEOWISE. Unfortunately, I did not and still do not have a lens that zooms enough to take the beautiful furrball photos of the tail that people have posted online. Nevertheless, I zoomed in as much as I could (45 mm.) and set up a shot containing NEOWISE against a foreground of some neighboring trees and rooftops. The first hints of sunlight had started to appear on the comet’s tail’s tail, and I knew that I had precious little time.

Another 10 clicks of this canvas, and I was satisfied, culminating in the picture at the beginning of this blog. I grabbed my binoculars for the last glimpses of the comet as the Sun slowly turned on the warm shades of dawn spotlight. My roommate, who’s always hungry post-stargazing, gently reminded me that the donut shop was about to open.

Part III: Photoshoots in Different Studios

July 14-24, 2020

A minor downside of astrophotography is that your camera is always in manual mode. It is set up to capture the target and only the target. If something interesting happens next to you, grabbing a shot will always give you terrible results - unless you are very deft with the dials or lucky with the settings.

For instance, imagine you are photographing a comet in the twilight sky, and have happily and comfortably positioned yourself next to a big dumpster. You see something moving out of it from the corner of your eye. It’s a big Raccoon (a.k.a. Trash Panda). Followed by another raccoon. And another. And another. Followed by an adorable baby raccoon. Ever seen an entire family of raccoons post-dinner?

They’re all walking towards you (are they blind!?). Slightly scared but also in awe, you want to click a picture of this fine raccoon family. You lift your tripod, flick out the screen and point the camera towards them. Their eyes eerily light up in the screen and soon they hear your movement and start scampering away. You manage to click the shutter button just in time to capture them all. However, the shutter never clicks! You curse as you realize that you had set the exposure time to 6 seconds to get the comet, far from the hundredths of a second that can pick out a running raccoon. What you end up with is an image of the last raccoon, completely out-of-focus and hence ghostly and blurry in motion:

The last raccoon. Can you see more?

The last raccoon. Can you see more?

Well, I don’t usually park myself next to dumpsters to look at raccoons. I did it only because it was the perfect vantage point to click a picture of comet NEOWISE right behind the big blue Ole Miss water tower. Having seen the comet aplenty and photographed it from the town center, my interest had turned towards getting snapshots of it against different foregrounds in Oxford. It felt like moving different studios to suit my model, rather than the other way around. A few great places I found were unfortunately not good for photographing thanks to excessive city lights. The comet, which had risen significantly above ground compared to a week before, looked quite amazing in the backdrop of the Lyceum, the main administrative building of the University of Mississippi. I could also see it behind the blue dome of the Kennon observatory. Both places, a bit annoyingly for the latter, have excessive street lighting that would saturate any long exposure photograph.

Desperately wanting to click NEOWISE behind something uniquely Ole Miss or uniquely Oxford, I stumbled upon the water tower next to the UPD building. It was at the correct location, with the red letters saying ‘Ole Miss’ pointed against the North East, where the comet would hover after sunset. Being atop a hill in one corner of the campus, there were not too many lights around. I ducked behind the short wall across the street from the tower to black light from the one streetlamp close to me. As luck would have it, this ideal position was right next to the dumpster, where unwittingly to me, the family of raccoons was chomping through their fifth course.

The stars of Ursa Major, where the comet resided that evening were beginning to appear. Including these would be important for the software that stacks my images, which uses stars for alignment. I took a few test shots to determine the position from where the comet would appear to be nicely raining down on the water tower from my perspective. Within minutes, it was dark enough for NEOWISE to start showing off its furry tail in my exposures.

It was time to get clicking. I adjusted the exposure time to around 4 seconds - long enough for the tail to appear but not too long to invite the glare on the glossy Ole Miss lettering on the tower. I also positioned the top bunch of leaves from a nearby tree to add a healthy serving of greens into the picture. This was what probably made the raccoons step out just as I was about to start clicking multiple pictures. After that silly diversion, I went back through all the steps to reconfigure my frame, and this time clicked a good 20 pictures to stack later.

One of the 20 raw images

One of the 20 raw images

As always, stacking all 20 pictures did a great job of bringing out the comet’s tail and starlight, while lowering the noise from each individual picture. I was extremely happy with the composition of the result. Finally, NEOWISE officially became a highlight of my time here at Ole Miss.

The final result, stacked and cropped

The final result, stacked and cropped

I made some other trips to hunt down the comet at different locations during that week, but without notable results. A disappointment worth remembering happened at Lake Sardis, where I convinced my colleagues of an unhindered view of the comet above the lake in complete darkness. What we encountered was a hazy sky where one had to squint to see the comet through binoculars. What more, the viewpoint on the road had plenty of lights that attracted plenty of bugs and mosquitoes. To make a bad night worse, I stepped on an ant hill on the way back to my car, and got feasted on. In comparison, a family of adorable raccoons is a disturbance I would invite for all my future quests.

Part IV: NEOWISE: a deeper look through a big telescope

In Astronomy, the deeper you peer, the more perspective you lose.

A lot of friends have told me that I’m lucky to have access to large telescopes and the ability to spend time with them clicking pictures. This is undoubtedly true! But I say that our natural pair of light-collectors give us some of the happiest moments while star-gazing. I believe in the power of naked-eye astronomy - it really enables us to reflect deeply on our place in the cosmos.

Take out time and observe the stars float around the sky from the East to the West, with the ones close to the pole star twirling around it. This helps you imagine the Earth rotate around its tilted axis. Next, turn your attention to the Moon and all planets visible and notice that they all lie along a single line across the sky. This is the Ecliptic line, cutting through what is the plane of our Solar System. Observe the planets over several nights, you’ll note that they hop slowly against the background of faraway, unmoving stars. Indeed, the word planet is derived from the Greek ‘planetes’, meaning wanderer.

If it’s a moonless late Summer or Fall night, you’ll likely see the mesmerising band of the Milky Way stretch across the sky. This showcases the greatest gathering of stars in the flattened disk of our spiral galaxy. Notice that the ecliptic is not at all aligned with the Milky Way band, telling us that our solar system is also inclined with respect to the plane of the Milky Way, even more so than the Earth is inclined with respect to the plane of the Solar System. Far from the flat and upright world around us, our life is spent being extremely topsy-turvy and fizzing across space at an incredible speed.

If you look northward from very dark skies late evening in Fall, you’ll see a ghost-like hazy patch suspended in the sky. In fact, you’ll only see it if you’re just trying to look away from where it actually is. The hazy elongated patch is in fact the Andromeda galaxy - the only galaxy visible to the naked eye besides our own. It’s so far away that it is hard to make out a single star in it; all we see is the collective faint blob of its central core. This means all the innumerable stars that we do see with our eyes all lie in our own galaxy. And once you realize that there are innumerable, invisible galaxies themselves scattered across the sky just like stars, it really makes you lose yourself in imagining the expanse of the universe.

To enjoy all of this, you need nothing more than a pair of eyes looking at clear dark skies. The night sky is filled with wonders, from the immovable stars in our galaxy, to wandering planets, from the stationary nebulous blobs of Andromeda (or if you’re in the Southern Hemisphere, the Magellanic clouds), to bright streaks of meteors fizzing across - blink and you’ll miss!

Then on occasion, there are beautiful visitors that act like slow-moving planet-wanders, but look wispy like distant galaxies, only brighter!

The best thing about NEOWISE was that it was a naked-eye comet, and as I’ve mentioned earlier, the first one since the late 90s. Its glimmer in the night sky was accessible to every single person without the need of expensive equipment - even better if one was far away from the city lights!

The best device to see a comet through is not a telescope, but a pair of binoculars. Indeed, one might call them the best stargazing equipment, providing a deeper look at some glorious objects while not losing much of the bigger perspective. They are also cheap and portable. I bought a pair of binoculars (named Cometron, by Celestron only a few weeks before NEOWISE appeared in the sky. Call me prescient! I actually got them for another comet, Comet SWAN, the appearance of which only made a few ripples in the amateur astronomy community before fizzing out. I hunted for it a few times and in the end I don’t think I ever caught sight of it. It was supposed to be close to Mercury after sunset one evening though, which gave me my first ever glimpse of the tiniest planet which is usually so difficult to see.

Anyway, after a couple of weeks when I had exhausted all my vistas of enjoyment with NEOWISE, through my bare eyes, binoculars and photography, time had come to point the biggest scope I had access to towards it. While the comet was hovering very low on the horizon initially, it soon gained enough altitude to be visible above the surrounding buildings from the rooftop telescope we have here at the Kennon Observatory, University of Mississippi. The telescope has the ability to magnify objects by more than a 100x. And while I have prepared you to dampen your expectations by downplaying big telescopes a little bit, I’ll admit that I gasped when I first saw it through the eyepiece.

Finding it took a bit of effort. I had to locate its position relative to the bright stars in Ursa Major (The Big Dipper) using Stellarium. I guided the scope using its remote control to the location where it was supposed to be. A look through the guide scope: a smaller telescope piggybacked on the big one to help us look at a larger chunk of the sky it’s pointed towards, showed a fuzzball already! I got it to the center of the guide scope, confident that it would now be visible through the eyepiece attached to the big telescope.

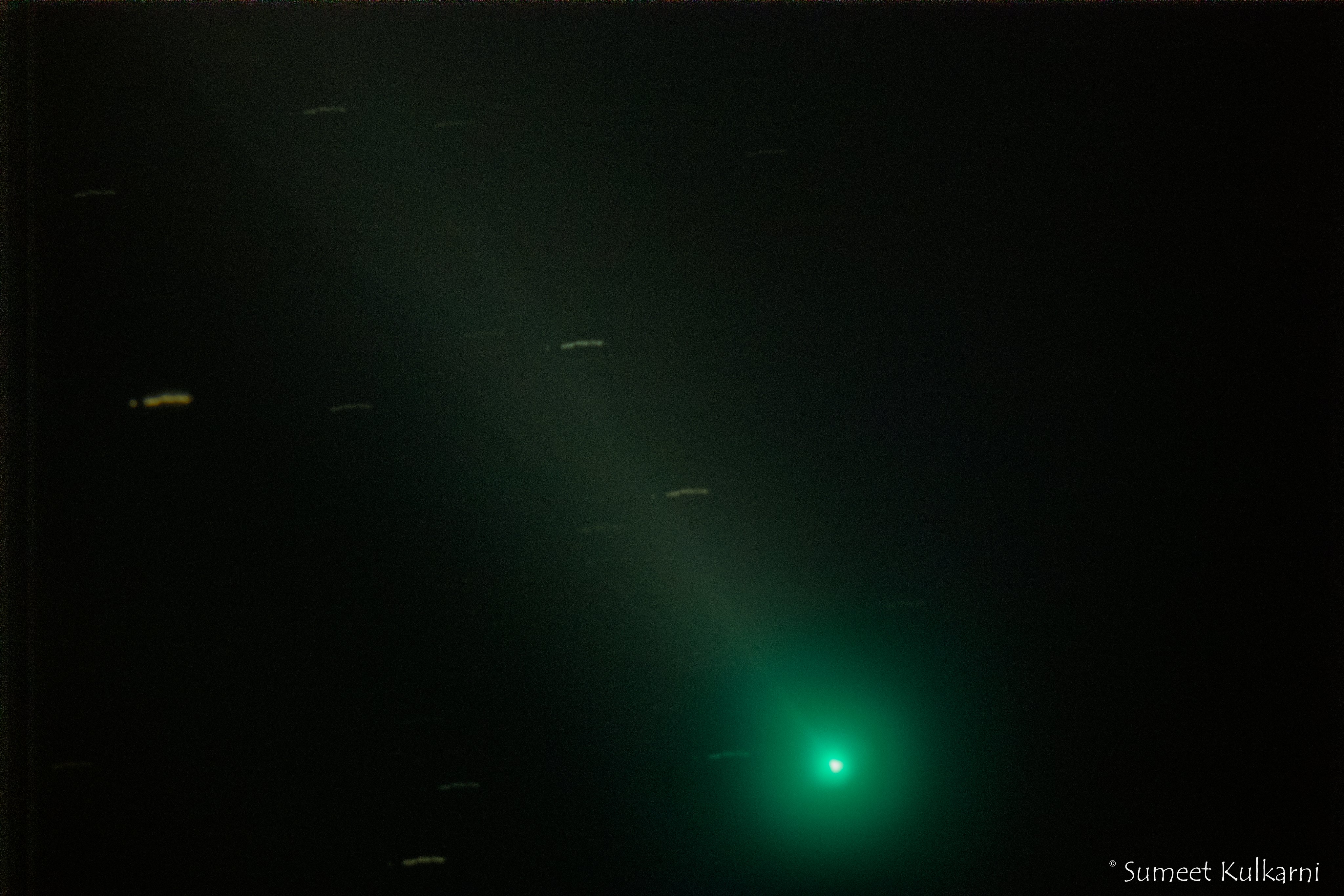

And wow, it looked just like Andromeda, just a little more compact, and a tad brighter. But what really stood out was the color of the haze: a resplendent emerald blue! Months later, I would see Uranus stand out with the same shade. But NEOWISE looked nothing like a comet. It was hard to discern its tail at all. But I knew that the tail was reserved for a view carrying perspective. The haze I saw was the core of the comet, the Coma . This was the blob of ice and rock that was fizzing across out solar system, trying hard not to melt away from its proximity to the Sun.

I tried my best to photograph the comet through the 12 inch telescope. In retrospect, I probably needed darker skies, more patience and more pictures. I did manage to take ~30 pictures, each around 5 seconds long (I no longer remember for sure). The problem with my lack of patience was that the field did not contain enough bright stars for the automatic stacking software, like sequator or deep sky stacker to work with.

But with the coma-haze clearly in view in all my shots, I could use the granddaddy of all photo-editing software, Adobe Photoshop to stack my pictures manually. Centering the coma in 30 pictures and adjusting their alignment for 30 pictures ain’t hard work, but it does test your patience. Also, I had to adjust the transparency of each successive picture as 1/n, n being the number of shots. If I were to just add all the light from all pictures together, I would end up with a bright mess. Stacking isn’t just aligning and adding; one needs to add exposures in a way that the signal builds up without over-exposure, while effectively cancelling the noise out.

So, the final result that I made you wait for? Here it is:

A big telescope, while not showing much of the tail, reveals the brilliant green nucleus (or coma) of NEOWISE. It’s the result of fluorescing carbonaceous gas molecules, including some poisonous cyanide!

A big telescope, while not showing much of the tail, reveals the brilliant green nucleus (or coma) of NEOWISE. It’s the result of fluorescing carbonaceous gas molecules, including some poisonous cyanide!

It still looks pretty great, if you ask me, for my first comet ;) You see a hint of the tail, but not its grandeur. Overall, it looks like a hex thrown towards the Earth by the heavens in 2020. By the color, it’s most certainly an Avada Kedavra. Too bad it missed us... Or did it?