The Spacetime Symphony...

When two black holes orbit each other, their extreme compactness and density causes ripples in the fabric of spacetime around them. These ripples, called Gravitational Waves, were first predicted by Albert Einstein in his general theory of relativity. But he never thought we could actually detect them---when these vibrations in spacetime reach the Earth from billions of light-years away, they become incredulously tiny. Physicists, however, like proving everyone wrong, be it Einstein. In 2015, the LIGO experiment---a pair of detectors, one in Livingston, Louisiana and the other in Hanford, Washington, which shoot lasers along L-shaped arms 2.5 miles in length along the ground---detected gravitational waves for the first time ever. These waves were given off by the motion of two black holes around each other, each about 15 times the mass of our Sun. The gravitational ripples carried energy away from the orbiting black holes, pulling them tighter, making them move faster, and thus creating even larger ripples. Eventually, they collided and merged to form one larger black hole that vibrated like a struck gong before settling down. This collision resulted in a huge amount of energy: for a fleeting moment, it was the most powerful event in the universe, more so than the combined light given off by all the stars in our universe! As the gravitational waves waves flew away into the cosmos and made their long journey towards the Earth, they weakened considerably, shaking the LIGO detectors by an amount smaller than the width of a proton.The direct detection of gravitational waves is an insanely precise endeavour, one that won the Physics Nobel Prize in 2017. My research within LIGO has traversed various aspects of this challenge, from using machine learning to tackle noise in the detector, to applying statistical data analysis techniques in figuring out the astrophysical properties of black holes hidden within the detected gravitational wave signals.

For a more detailed introduction to the physics behind gravitational waves, I have created this this interactive learning module:

A lot of physics concepts taught at the middle- and high-school level are also applied in cutting-edge research such as the detection of gravitational waves by LIGO. This online, interactive module uses Streamlit, a python-based library to connect the astrophysics of black holes to the properties of waves that they emit, forming a toolkit for teaching physics in an engaging way.

Link:

https://gravitational-waves-tutorial.streamlit.app/

Summary of Research Projects:

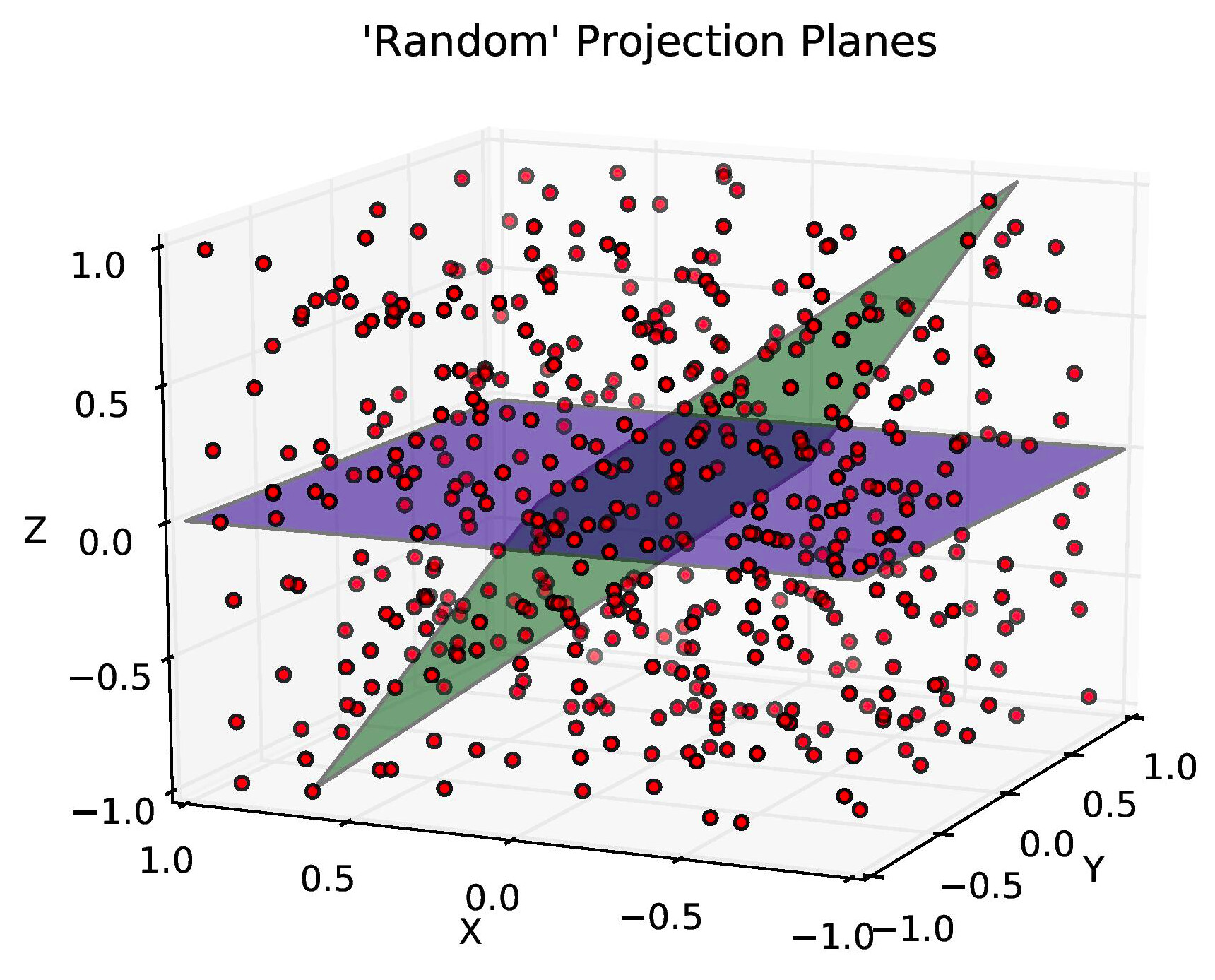

Random Projections

My Masters' Thesis project borowed the idea of Random Projections from data science. In broad terms, it says that the structural distribution of high volumes of data is retained when we transform or project it randomly into a lower-dimensional subspace. The relationship between any two data points, for instance, how far apart they lie, is not affected by this projection, making it a lot easier to carry out data analysis with lesser computing power. I applied this technique to the needle-in-the-haystack search for gravitational waves. You can read more about my work in the article published in Physical Review D. Open Access available on ArXiv

My Masters' Thesis project borowed the idea of Random Projections from data science. In broad terms, it says that the structural distribution of high volumes of data is retained when we transform or project it randomly into a lower-dimensional subspace. The relationship between any two data points, for instance, how far apart they lie, is not affected by this projection, making it a lot easier to carry out data analysis with lesser computing power. I applied this technique to the needle-in-the-haystack search for gravitational waves. You can read more about my work in the article published in Physical Review D. Open Access available on ArXiv

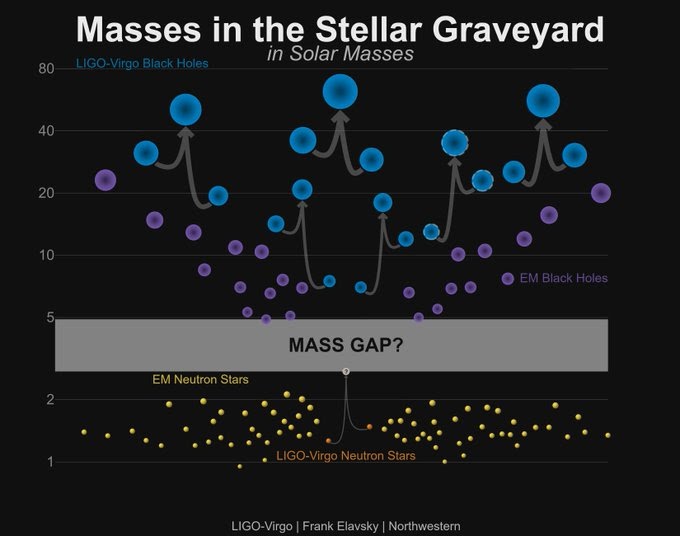

Explaining the Mass Gap

We do not know where the dividing line between neutron stars and black holes lies in terms of their mass. Theoretically, the heaviest a neutron star can be is about three times the mass of the sun. The lightest black holes we’ve seen weigh around five solar masses. We’ve never observed anything using telescopesin the space between three and five—a range we call the 'mass gap'. That is, until now. The LIGO-Virgo gravitational wave observatories have detected compact objects with masses in this range. We are still unsure whether they are heavy neutron stars or lightweight black holes. It is still unclear on how they form. One possibility is of them being 'second-generation' compact objects formed out of the merger of two smaller neutron stars. I'm working on creating models to explain how the mass gap objects we are detecing in LIGO-Virgo may have formed, and how many we could detect using future, 3rd generation gravitational wave detectors.

We do not know where the dividing line between neutron stars and black holes lies in terms of their mass. Theoretically, the heaviest a neutron star can be is about three times the mass of the sun. The lightest black holes we’ve seen weigh around five solar masses. We’ve never observed anything using telescopesin the space between three and five—a range we call the 'mass gap'. That is, until now. The LIGO-Virgo gravitational wave observatories have detected compact objects with masses in this range. We are still unsure whether they are heavy neutron stars or lightweight black holes. It is still unclear on how they form. One possibility is of them being 'second-generation' compact objects formed out of the merger of two smaller neutron stars. I'm working on creating models to explain how the mass gap objects we are detecing in LIGO-Virgo may have formed, and how many we could detect using future, 3rd generation gravitational wave detectors.

Inferring the spin tilts of Black Holes

You may be wondering why the black holes on this page have arrows on them? These arrows represent the spin axes of rotating black holes. Just like the Earth spins around an axis that is tilted with respect to its orbit around the Sun, black holes orbiting each other also have their spins inclined. Further, since they're moving rapidly, they can influence each other's spins, causing them to precess like a spinning top. In my research, I simulate these black hole spin tilts forward and backward in time, using full numerical relativity models as well as its approximate solutions at large separations. Evolving black holes backward in time and looking at how their spins are inclined can help us understand how such binary systems form.

You may be wondering why the black holes on this page have arrows on them? These arrows represent the spin axes of rotating black holes. Just like the Earth spins around an axis that is tilted with respect to its orbit around the Sun, black holes orbiting each other also have their spins inclined. Further, since they're moving rapidly, they can influence each other's spins, causing them to precess like a spinning top. In my research, I simulate these black hole spin tilts forward and backward in time, using full numerical relativity models as well as its approximate solutions at large separations. Evolving black holes backward in time and looking at how their spins are inclined can help us understand how such binary systems form.

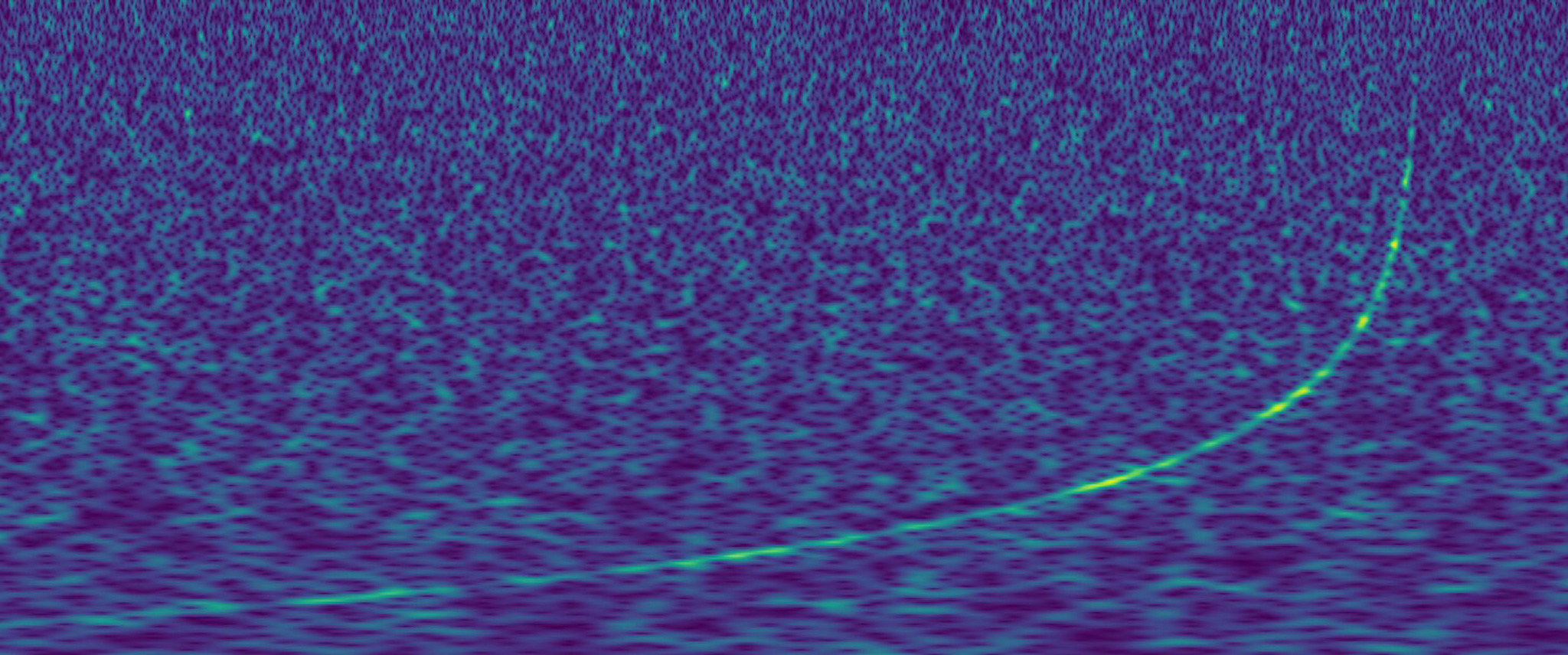

NNETFIX: A Neural Network to 'Fix' contaminated Gravitational Wave signals

The increased rate of detections by the Advanced LIGO and Virgo observatories means that incoming gravitational-wave signals more likely to be overlapping with or contaminated by glitches: transient noise bursts that frequently affect the detector for a variety of reasons, like wind, earthquakes, laser scattering, or even birds pecking at ice forming on the detector

wall! The presence of a glitch on top of a signal distorts our initial estimation of the source parameters, particularly the sky position.

This means we cannot send accurate alerts to our astronomer friends to search for it. I have developed a scikit-learn basedneural network

to subtract an overlapping glitch from an astrophysical gravitational-wave signal. The method cuts off the glitch and identifies features of the gravitational-wave signal to 'fill in the gap' and reconstruct the portion of the data affected by the glitch.

The increased rate of detections by the Advanced LIGO and Virgo observatories means that incoming gravitational-wave signals more likely to be overlapping with or contaminated by glitches: transient noise bursts that frequently affect the detector for a variety of reasons, like wind, earthquakes, laser scattering, or even birds pecking at ice forming on the detector

wall! The presence of a glitch on top of a signal distorts our initial estimation of the source parameters, particularly the sky position.

This means we cannot send accurate alerts to our astronomer friends to search for it. I have developed a scikit-learn basedneural network

to subtract an overlapping glitch from an astrophysical gravitational-wave signal. The method cuts off the glitch and identifies features of the gravitational-wave signal to 'fill in the gap' and reconstruct the portion of the data affected by the glitch.

Calculating the "kicks" of Binary Neutron Star remnants

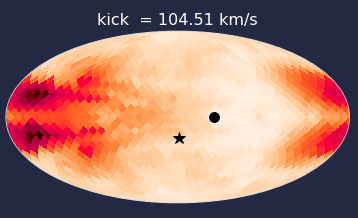

When two neutron stars merge, they also radiate gravitational waves before forming a remnant object which is typically a black hole. This collision is accompanied by an explosion of matter known as a kilonova around the black hole. This mass often ejected asymmetrically. The emitted gravitational waves are also not symmetric unless the two neutron stars are exactly the same. Due to conservation of momentum, the remnant black hole gets recoiled (or "kicked") in a direction opposite to the ejection of matter and the radiated gravitational waves. If these kicks are too large and exceed the typical escape speeds of galaxies, the black hole can get ejected. Using state-of-the-art general-relativistic magnetohydrodynamic (GRMHD) simulations, we have estimated the magnitude of such kicks in binary neutron star remnants for the first time. The image on the left represents the distribution of ejected matter around the remnant black hole in the center, drawn on a mollweide projection (like a world atlas). The darker patches indicate places where there is more ejecta, while the star represents the direction of the kick.

When two neutron stars merge, they also radiate gravitational waves before forming a remnant object which is typically a black hole. This collision is accompanied by an explosion of matter known as a kilonova around the black hole. This mass often ejected asymmetrically. The emitted gravitational waves are also not symmetric unless the two neutron stars are exactly the same. Due to conservation of momentum, the remnant black hole gets recoiled (or "kicked") in a direction opposite to the ejection of matter and the radiated gravitational waves. If these kicks are too large and exceed the typical escape speeds of galaxies, the black hole can get ejected. Using state-of-the-art general-relativistic magnetohydrodynamic (GRMHD) simulations, we have estimated the magnitude of such kicks in binary neutron star remnants for the first time. The image on the left represents the distribution of ejected matter around the remnant black hole in the center, drawn on a mollweide projection (like a world atlas). The darker patches indicate places where there is more ejecta, while the star represents the direction of the kick.

List of Publications

- S. Kulkarni, N. K. Johnson-McDaniel, K. S. Phukon, N. V. Krishnendu, A. Gupta. 2024. Inferring spin tilts of binary black holes at formation with plus-era gravitational wave detectors. Phys. Rev. D 109, 043002. e-Print: arXiv:2308.05098

- S. Kulkarni, S. Padamata, A. Gupta, R. Kashyap, D. Radice. 2023. Numerical Relativity Estimates of the Remnant Recoil Velocity in Binary Neutron Star Mergers. Phys. Rev. D 108, 103023. e-Print: arXiv:2308.03955

- S. Kulkarni, B. Whitworth. 2022. Podcasts in Science Classrooms: Story-telling for All Ears! The Physics Teacher, 60(6):419–421

- N. K. Johnson-McDaniel, S. Kulkarni, A. Gupta. 2022. Inferring spin tilts at formation from gravitational wave observations of binary black holes: Interfacing precession-averaged and orbit-averaged spin evolution. Phys. Rev. D, 106(2):023001. e-Print: arXiv:2107.11902

- S. Kulkarni, S. Padamata, A. Gupta. 2022. Recoil Velocity of Binary Neutron Star Merger Remnants, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 2020;16(S363):250-254. doi:10.1017/S1743921322002022

- H. Kumar et al. including S. Kulkarni. 2022. India's First Robotic Eye for Time-domain Astrophysics: The GROWTH-India Telescope. The Astronomical Journal, Volume 164, Number 3. e-Print: arXiv:2206.13535

- K. Mogushi, R. Quitzow-James, M. Cavaglia, S. Kulkarni, F. Hayes. 2021. NNETFIX: an artificial neural network-based denoising engine for gravitational-wave signals. Mach. Learn. Sci. Tech., 2(3):035018. e-Print: arXiv:2101.04712

- A. Singhal et al. including S. Kulkarni. 2021. Deep Co-Added Sky from Catalina Sky Survey Images. MNRAS, Volume 507, Issue 4, November 2021, Pages 4983–4996, e-Print: arXiv:2108.00029

- S. Kulkarni, K. S. Phukon, A. Reza, S. Bose, A. Dasgupta, D. Krishnaswamy, A. Sengupta. 2019. Random projections in gravitational wave searches of compact binaries, Phys. Rev. D 99, 101503(R). e-Print: arXiv:1801.04506